Causal 4: Precision vs. Accuracy (Planning Anti-patterns)

This post is a sympathy piece for people who get asked to commit to a level of detail in plans, schedules, and roadmaps they suspect is too much.

A common anti-pattern in planning is to act as if precision is valued over accuracy. The more specific the plan, the better. Right? After all, detailed plans with all the possible work-items detailed, all with names of who will do that work, is evidence of great thought. The Gantt chart and roadmap filled with dates and promises knows all.

There are many tools out there designed to try to minimise this sort of ‘interference’ (for example, see “Now, Next, Later” roadmaps) from managers - instead I would like to explore closer to what I believe is the root of the issue.

Consider that our thinking power is perhaps why we are hired as systems engineers and product people - these are both complicated and complex disciplines. And we often sit in a unique position in the middle of it all, the one group of people able to unravel the mess. If this is true, it’s no wonder that managers (project or otherwise) want to see evidence of our thoughts.

Let’s consider some of the implications of this premise.

Now. If we really are in a privileged position of seeing the whole picture in a way that no one else can - how must it feel for the people who aren’t us? Especially the people who strongly suspect something is behind the curtain but don’t have the skills, knowledge, experience, or otherwise to take a peak. They know that what we’re trying to accomplish is hard and messy. This could well be worrying, confusing, or anxiety-inducing. How can you trust something you don’t understand?

Build understanding to plug the confidence gap

Storytelling is well documented in product management - it’s about helping bring both your users and your stakeholders on a journey.

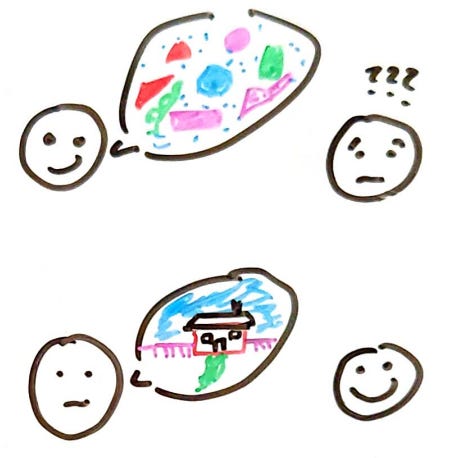

Which would you rather hear? Accurate and complex or clear and precise.

For your senior stakeholders, life is filled with worry. There’s a big team, spending lots of money, and making many decisions. Who knows whether any of this is good, bad or ugly. Worse still for them, they are far away from the coalface. As experts in navigating the mess, we know it’s hard enough to help designers and developers align on what matters, so how can your senior executives have any hope when they spend a fraction of their time in your work?

I hypothesise that Gantt charts and highly detailed plans are proxies for evidence you have thought about the challenge at hand. This need to ‘see the plan’ is often dressed up as a request for information: I need to know so I can tell the leadership, I need to know so I’m informed about what to expect, so I can plan.. Sometimes these things are true - but, if these are familiar arguments to you, consider the last time anyone took action based on the information in the Gantt chart. If any action was taken at all, was it a sweeping re-assessment of the business viability based on the fact that you’re projecting a 6 month slip? Somehow, I doubt it. More often, it’s used as a conversation piece - something that is easy to look at and challenge. You said X was going to be finished by now, why is it still not done? For better or worse, Gantt charts make it easy to engage with something that is potentially otherwise intangible and complex. They are precise.

Senior stakeholders are not naive enough to expect they could possibly understand everything you do - so they ask for schedules and plans to help simplify. They are seeking something that shows you have thought about it, something that fills the confidence gap, something that helps them participate. The easy thing to ask for (because you don’t actually need to know anything about the work to be able to ask for it) is to tell me what you will do next. The Gantt chart. And precision often means detail - more specific information - which is surely comforting evidence that you’ve put a lot of thought into it. Remember, you understand the details of the mess - your manager might not. And if they don’t, they aren’t in a position to effectively judge which of the details might be accurate, and which are wild speculation. Hence, accuracy is ignored in favour of precision.

So, can we do better? I propose that you start by acting with empathy. Assume that senior stakeholders asking for fantastical plans filled with fantastical promises mean well, and that they want to help but that the mess gets in the way. Instead of simply pushing back and saying ‘Now Next Later’ is your new way of doing roadmaps - spend more time building more confidence in your way of working and why you are confident. Spend time helping people understand that, when it isn’t going well, you have ways to detect that, and you’ll be able to make changes in a way that will trend positive. Spend time helping your stakeholders understand how they can help you. Be proactive and give them ways to engage that are more helpful, instead of leaving them to waste time probing why a feature slipped two weeks only to find some of the team are out sick.

A specific suggestion is to consider communicating some of the risks in your work. And I don’t just mean “there is a risk we won’t deliver on time” - be much more specific than that. Why might you not deliver on time? Because you don’t have enough staff? because some of your dependencies aren’t being met? Why might that be the case? Then explore how you might be able to mitigate, and how can your manager help.

Plug the confidence gap and the participation gulf.

Help them, help you.